It’s hard to argue global supply problems are improving, but in the words of the theologian Thomas Fuller, it’s always darkest before the dawn. As covered last quarter, supply chains are slowly healing and getting better.

Freight rates have since declined from their late 2021 high, and although delays and schedule reliability are still a world away from where they were before the pandemic, there’s been a positive trend. The lockdown measures initiated by governments in an effort to contain the spread of Covid-19 have all but stopped, which means manufacturers are once again running smoothly and without interruption.

Labour shortages that had caused bottlenecks at ports and distribution centres are overall easing, with the number of people in transport now returning to pre-pandemic levels. Sea freight has added capacity during the past two years, while the lost airfreight capacity has reemerged as passenger traffic, which was routed to the sea when flights were grounded, returns to air. All of these taken together should translate into visible improvement in the situation since the second half of 2022.

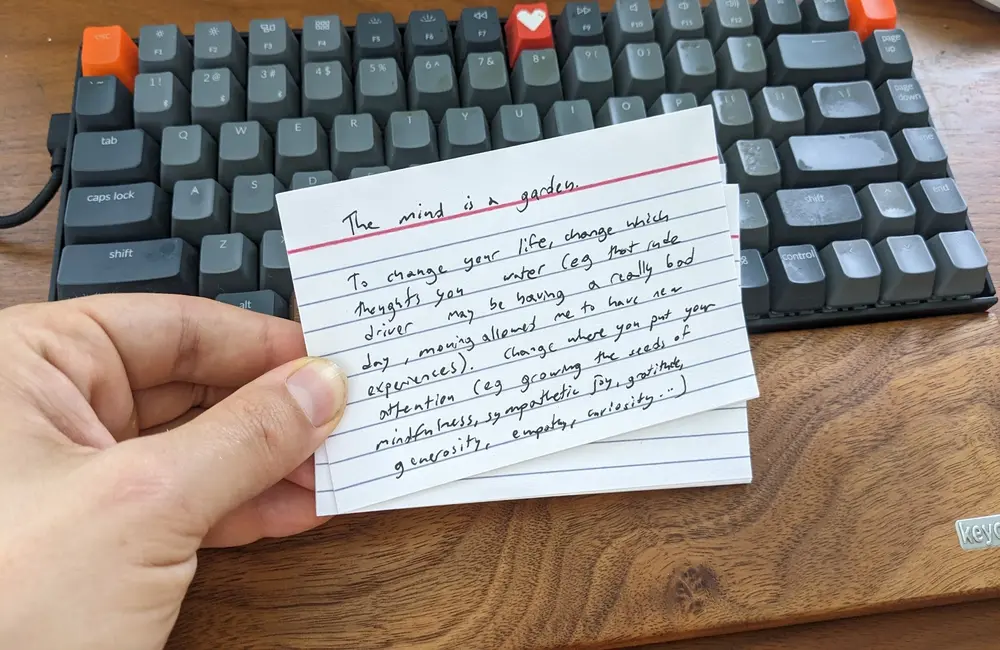

Corporates globally are diversifying supply chains to prevent the breakdowns of last year from happening again. The percentage of survey respondents who for example had introduced dual sourcing rose from 55% months ago to 80% recently [1].

It might not seem like it, but supply chain issues are slowly getting better.

Reasons to be optimistic

Ocean freight reliability is showing improvement, with fewer delays, but off a high base in 2021;

All of the root causes of the supply chain crisis lockdowns, social distancing mandates and labour shortages are better than they were six months ago.

Sea and air freight capacity is expanding through 2022, which may relieve shortages, especially on east-to-west routes;

Ship freight rates, which are down dramatically off their late 2021 highs, should continue a trend of declines into H2 ’22, which should ease some pressure on global inflation rates;

Automaker suppliers: Car manufacturers are increasing collaboration with chipmakers and scaling technology as a longer-term solution to the pandemic-induced shortages. And semiconductor inventories are beginning to rebuild slowly, as the producers are running plants hard and investing in new facilities to meet increased demand that should hit its peak this year.

Some caveats

That does not mean all our supply chain woes have gone away.

New surveys of businesses across the European Union by the European Commission show material and equipment shortages as a limiting factor on production for 2022, and would inflict heavy pain on recovering industries. Removing those backlogs at ports all over the world will also take time. Another inflationary headache related to high freight rates is one that will take a long time to get over.

Many customers have been locked in to longer term contracts at high rates, with many of these costs passed onto the end consumer through increased prices on shipped goods. It goes some way, at least, to understanding the current inflationary crisis we are in, which has seen central banks worldwide raising interest rates in an effort to cool spiraling rates of inflation.

In the medium run even, we remain at risk to these exogenous shocks, with already adding to the frustrations and strain to the system at Autumn 2023 with recent and still ongoing Russia-Ukraine war; entire city of Shanghai locked down; China struggles to get in front of their own zero-infection covid policy.