Asian equity markets are increasingly globalised, new research from Index group has found. It is Japan, China, Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore that are all making more than last year. Asia is following a global trend. Of the 48 national equity markets covered by indices across Asia Pacific, Europe and the Americas, only 18 have grown in their domestic focus.

The Japanese stock market now makes 45% of its revenues outside of Japan, up from 43% when we looked in June 2021; China went from 9% international to 10%, South Korea from 52% to 53% international; Hong Kong from 59% to 58% international; and Singapore from 50% to 51% international.

Deeper globalisation is hardly the prevailing story of the day. We inhabit a "postglobal world," as the title of a new book has it, one in which the direction of travel is "localisation". Meanwhile, the latest issue of The Economist centers on “reinventing globalisation.”

“Offshoring,” a popular term of the ’90s and ’00s, is now a dirty word, and “onshoring,” “reshoring” and “slowablisation” are in vogue. Political tides had already turned against globalisation even before the pandemic, inflation and the war in Europe revealed the vulnerabilities of global supply chains. Independence and self-reliance are in the ascendant.

Seeking Out Revenue Streams Across Borders

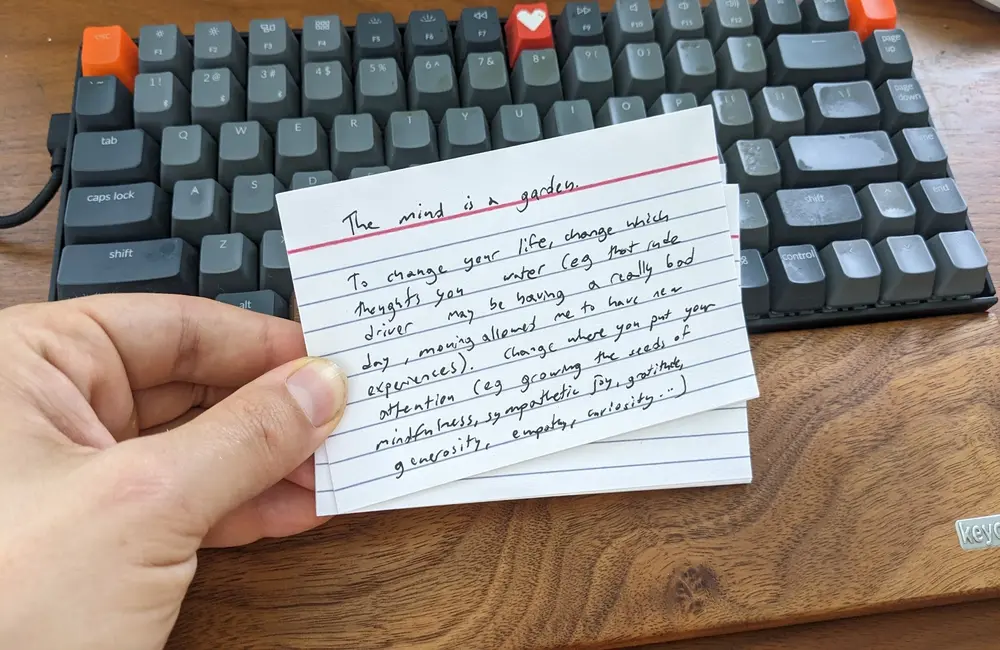

1: Pooh-pooh bonds, and be bullish. Don’t scapegoat bonds to explain what’s going on: It certainly is odd that equities and Treasuries are being bid up, but stock-market fans are very excited about the wave of cash that will crash into Wall Street when it passes much more exciting than what happened last spring when virus-stimulus money went to the people instead of the markets like good little stim money. To understand what’s going on, remember the truism that stock markets are markets of stocks. Market level trends are led by the behaviour of the underlying businesses.

Think of Keyence, a Japanese maker of electric devices, whose sales outside Japan, including in China and the US, increased more than its domestic sales in the past year, helping to globalise Japan’s market.

EMs Remain the Most Domestic

The world’s four biggest equity markets (the US, Japan, the UK and China) all get a greater proportion of their revenue from international markets now than they did at the same time last year. None of the shifts were large. Japan, meanwhile, dipped from 57% domestic a year ago to 55% this year. The U.K. went down from 27% to 25%, and China from 91% to 90%.

According to one report, Egypt, Pakistan, China, Peru, Indonesia, the Philippines and the Persian Gulf were among the markets that have been least exposed to the world economy. The China Index, despite China being an export-oriented economy, derives an estimated 90% of its revenue from China partially attributable to its top contributors including Tencent (TCEHY ), Alibaba (BABA), Meituan (MPNGY), China Construction Bank (CICHY), JD. com (09618).

European markets are still the world’s most outward looking. European companies and markets are overwhelmingly global, apart from Greece which is mostly domestic.

The most global of these is the Switzerland Index, its components include Switzerland’s three largest firms by market weight: Nestle, Roche, and Novartis, with the US representing an estimated 30 percent of its revenues. Strikingly, the Dutch Index sources even more revenue from Taiwan (some 13%) than it does in its home country (10%).

It’s less remarkable to see small countries, such as Ireland and Denmark, among the world’s most outward-oriented, than it is for larger economies like France, Germany and the UK. Revenue coming from the US (about 22%) and China (9%) follow but other European countries are the single largest revenue source for the Europe Index.

Economic sectors don’t appear to be functioning as heavy drivers of change from a year ago. Sector secularities vary strikingly from deserts all around, not so much. The technology sector is the most global, and utilities, in real estate and financials are the most domestic.

But some resources-heavy markets globalized while others did not, including Australia, Brazil, Chile and the United Arab Emirates did, as did Canada, Peru, Saudi Arabia, Norway, South Africa and Qatar in other words. This is a global market for resources, after all, so surely producers would find a way to monetise their newfound international revenue potential in an era of high prices and surging demand. And, similarly, some tech-heavy countries globalized the US and South Korea among them and others like Taiwan and India did not.

Revenue Streams Obfuscate the Distinctions

Some no doubt will, but the trend of globalization in equity markets contrasts with the narrative that supply chains are onshoring and countries are seeking self‑sufficiency. But the stock market is not the economy. “Revenue for public companies is only part of the mosaic. There are many other ways to measure economic globalization including the most common, trade as a percentage of gross domestic product.

For investors, globalised sources of revenue make it harder to separate a portfolio’s domestic and international components. While it is the case that global exposure can be achieved in many cases through domestic firms, it is also the case that in some cases the biggest domestic players in their sector can be headquartered offshore. Once again, the broadest opportunity set inhabits a global portfolio.