The path to making money in emerging markets is riddled with potholes, speed bumps and tolls. The hazards confronting investors in these markets are numerous and acute.

In the 10 years to February 2022, the standard deviation of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index was 20% greater than the MSCI World Index (a proxy for stocks in developed markets globally). But conventional indicators of risk fail to capture the litany of risks in emerging markets, which run the spectrum from poor governance to political strife. They also do not scale the trading costs and taxes of accessing these markets.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the response from governments around the world is the latest risk to spook emerging-markets funds. Governments have put in place a variety of economic sanctions on Russia as of this writing. But the impact on financial markets is much more complex. The Moscow Exchange is still closed, while European and US exchanges have suspended trading of some depositary receipts of Russian companies listed in those countries. Investors who need (or need) to dump these assets may not be able to do so and if they can, those trades will cost a lot.

Not ideal, to be sure, but the effect on investors in broad emerging-markets funds should be limited, with Russian stocks and bonds making up only a small percentage of the affected portfolios. But it’s a reminder that incremental risks face emerging markets, as this historical montage suggests.

Prevalent political corruption

Some of the latest, and certainly among the most visible on-going examples of corruption in the emerging markets emerged in late 2015. Brazil's state-owned oil company known as Petrobras (PBR) was accused of using its contractors to pay bribes in a network of payments between Brazil's politicians and company executives. The scheme siphoned millions of dollars from the company, while lining the pockets of various individuals, including Brazil’s former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who later went to prison.

Wrongdoing by corrupt executives at emerging-markets companies is old hat. These were common in late 1990s Russia as its economy was trying to make the leap to capitalist democracy. In late 2000, investors learned that Gazprom, the state-controlled natural gas giant in Russia, had sold off dozens of significant reserves of natural gas to insiders, including its executives and their families, for pennies on the dollar.

The firms also have one other important distinguishing property that rises risk. Petrobras and Gazprom are state-owned enterprises: companies that are partly or fully owned by their respective governments. State ownership is much more common in emerging markets versus developed economies. You won't find many state-owned companies in countries in the developed world, while estimates have them making up just over 20% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

This increases risk as politicians do not always pursue the same goals as investors. Corporations have a quite narrow task of maximizing profits for shareholders, whereas the responsibilities of governments include resource security, foreign policy and social welfare, among others. Higher wages might be good for workers and the local economy, but they suppress companies’ profits.

In 2012, state ownership risk became very high on the agenda when the Russian government mandated cash dividend payments of 25% of net income to shareholders for its SOEs. Thus many emerging-markets dividend strategies had big country allocations to Russian stocks.

Wisdom Tree Emerging Markets High Dividend ETF (DEM), whose strategy weights stocks by annual cash dividends paid, saw its stake in Russian stocks surge to almost 20% by mid-2013 from 1.3% in December 2011. Energy shares moved in the same direction because the Russian economy has a significant share of energy. The timing could hardly have been worse since the move amplified the fund’s volatility when oil prices fell in 2014 and 2015.

The threat in this case was not necessarily the precise result of a greater position in the Russian market. But that shows the degree of influence governments have over how a state-owned enterprise uses its profits. And while its dividend mandate rendered ZAR962 billion of Russia’s SOEs more attractive on a dividend-yield basis, it also locked up retained earnings that might have been used to create value by reinvesting in operations, paying down debt or expanding through mergers and acquisitions.

A rotating cast of characters

Emerging-markets economies are fickle than their developed-markets cousins in the United States, Western Europe and Japan. That makes their stock markets volatile, and can result in the shutting down or even crashing of entire markets. In fact, country membership rotates with a higher frequency in the emerging-markets universe than it does in developed markets, resulting in greater portfolio turnover.

We don’t need to go that far back through history to find the same examples. Stocks traded in Venezuela and Argentina were deleted from the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in 2006 and 2009, respectively, when their markets became harder to trade. Greek stocks were introduced late in 2013, after a downgrade to emerging from developed status following the country’s debt crisis. Stocks from Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia were added to the mix in recent years.

Most of the places that slosh in and out of the emerging-markets universe are niche markets, so pending changes won’t have much impact on what an index fund holds. But that also means those stocks are less liquid and more costly to trade.

Trading and taxes

Finding a cheap and easy way to trade emerging-markets stocks can be difficult. These markets are less liquid; there are currency considerations; there might be transaction taxes; and we’ve seen cases where local dislocation has made some close for a long time.

In terms of the exchange-traded fund structure specifically, exchanges in markets such as mainland China, South Korea and Brazil (among other destinations) ban in-kind redemptions, one transaction that would enable ETF managers to cleanse their funds and remove securities on which unrealised capital gains had built up, without having to make taxable distributions to investors. This process is the key to ETFs’ tax efficiency.

ETFs that track stocks in these particular markets have to sell shares directly to the market and pass along any capital gains to shareholders, leaving them with an unwanted tax bill, possibly. VanEck Vectors China Growth Leaders ETF (GLCN), a fund that owns stocks off the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges in mainland China, made one of the most egregious capital gains payouts of 2018. Its 2018 distribution was 8% of the fund's closing net asset value as of December 31, 2018.

Riskier, but not unreasonable

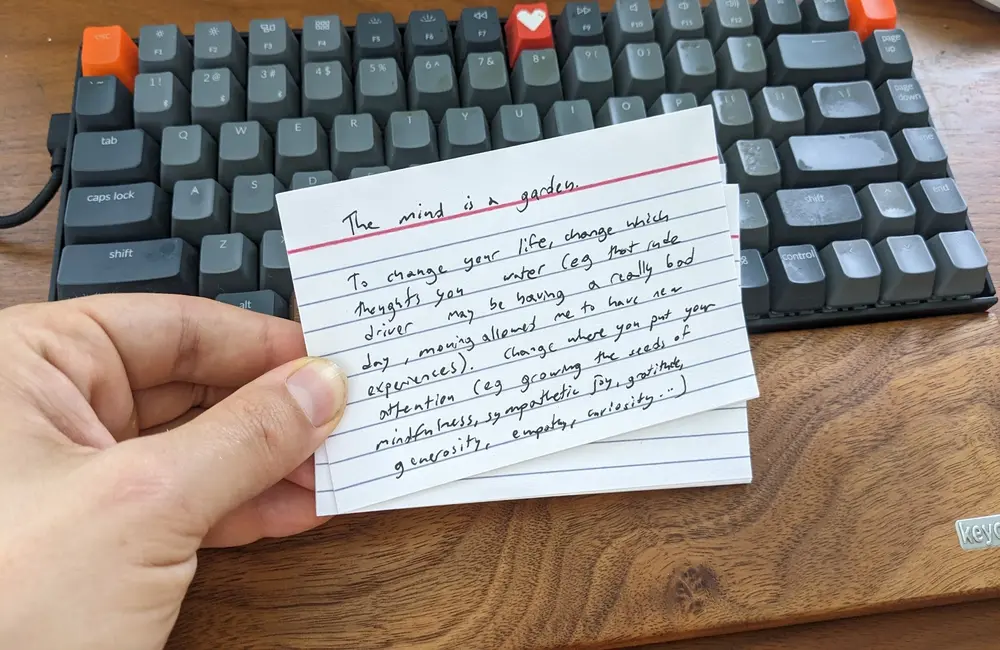

These risks don't exactly make for rosy reading, but investors shouldn't write off emerging markets altogether. At the very least, increased risks drive home the need for diversification in investing in emerging markets.

Best to go with broad-market index funds that diversify their holdings among a range of stocks and countries. But increased risk in these markets lowers our conviction that broad-market index funds can beat their Category average.