Such a turn to hawkishness caught markets off guard. As revealed in minutes from the Fed’s December policy meeting, released 5 January, the documents also indicated officials broached the idea of lifting rates “sooner or at a faster pace” than previously expected.

Stocks and bonds immediately sold off. Three weeks of declines have pushed first the tech-heavy Nasdaq and now the S&P/ASX 200 into correction territory, defined as a fall of more than 10 percent from a previous closing high.

Often called “quantitative tightening,” the policy is the opposite of “quantitative easing,” or the large-scale buying of bonds and other securities by central banks to lower long-term interest rates and stimulate credit.

Why now?

And the Federal Reserve is rolling back its unprecedented support as inflation rises and the economy continues to recover post-pandemic.

Monetary stimulus since the pandemic took two forms: near-zero interest rates and quantitative easing.

But with US consumer prices now rising at the fastest rate in 40 years and the labour market approaching so-called “full employment”, they want to change tack.

Interest rates are already expected to go up, with Fed officials indicating four or more rate increases in the year ahead. The first one is expected in March, according to market participants. QE asset purchases will also end then, and by that point the Fed will own nearly $9 trillion in assets, half purchased since the pandemic began.

The next is to pull that back. The Fed’s policy making committee said on Thursday that it had laid out plans for QT, adding that it anticipates being able to begin once it has started hiking rates. No firm timeline is in place. Market participants say the move is possible in the second half of the year.

How will it work?

In guidelines released Thursday, the Fed said it wants a policy known as “runoff,” in which the central bank does not reinvest the proceeds from maturing bonds.

Today, the Fed reinvests the money in new assets when bonds mature. This maintains its total amount of holdings constant. Allowing bonds to mature without reinvesting the proceeds will gradually shrink the number of assets on the Fed’s balance sheet; that process is known as runoff.

One alternative would be to sell bonds and other securities outright, but the Fed has said it “primarily” plans to pare its holdings through runoff.

Officials will probably lend and drain in relatively small amounts at first and fix monthly runoff limits so as not to rattle bond markets used to the Fed’s buying presence. Committee member Raphael Bostic favoured a pace of $100 billion a month, he noted in comments two weeks ago.

How will it impact markets?

QT unwinds the stimulus created by quantitative easing. Central bank QE programs purchased trillions in bonds and other securities, driving down yields, which go lower when prices go higher. Low yields encouraged borrowing and lifted equity valuations as the purchases created liquidity in the banking system.

Years of quantitative easing turned central banks into key players in the government debt markets at the base of the financial system. By December 2021, the Fed owned about a quarter of the $23 trillion dollar US Treasury market. At home, the Reserve Bank holds roughly a third of the $800 billion federal government bond market.

Stopping purchases means that central banks are taking out a massive demand source from bond markets. That could boost bond yields, and make borrowing more expensive and hit equity valuations.

“If the RBA disappears from the market, isn’t there buying bonds, isn’t there supporting the price of bonds, everything else being equal, yields will rise as a big buyer has been taken out of the market,” says Stephen Miller, an adviser to GSFM funds management.

“That’s what’s going to happen when the Fed ends its quantitative easing program, too. The same when the European Central Bank does it and the same when the Bank of England does it.”

Bond yields are already climbing in expectation of the shift. US 10-year government bond yields rose 25pc and Australian 10-year yields are up 29pc over the past month.

This isn’t the first time the Fed has trimmed its balance sheet, and bad memories from that round might also be haunting markets. The last time the Fed kicked off QT, in 2017, it drained $600 billion across two years before an interest rate spike in short-term borrowing markets indicated too much liquidity had been sucked out. The program was put on hold in late 2019.

It will be technology that feels the brunt first

Technology stocks, the most sensitive to rising bond yields, are the first to experience the impact of a shrinking of central bank balance sheets, according to Miller.

With regard to tech companies, much of company value is in future earnings. As investors discount those future earnings at a faster pace (thanks to higher bond yields), the present value for these stocks declines even further and faster than the overall market.

U.S. technology stocks have led the selloff as the Nasdaq Composite has fallen 14.5% this year, versus 9.3% for the broad-market S&P 500.

Other sectors that will likely show difficulty with higher interest rates include infrastructure and real estate investment trusts (REITS). These features of “bond surrogate” sectors mean they become less attractive to investors when yields get higher and income from fixed interest improves, according to Graham Hand, managing editor at Firstlinks.

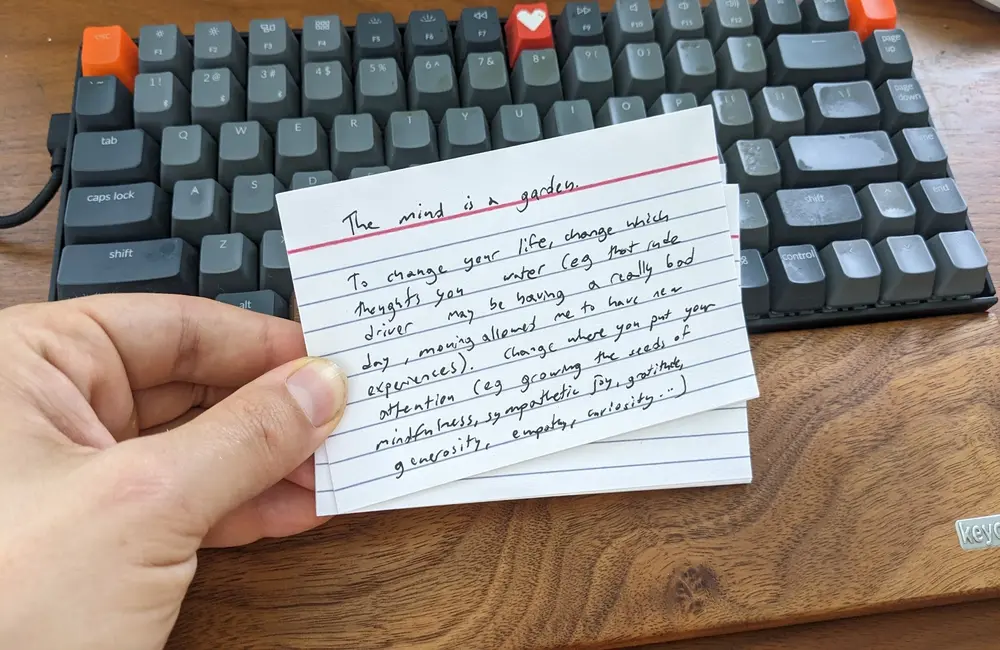

It could set a precedent for Reserve Bank

Every eye is on the Federal Reserve, but a cut to the Reserve Bank’s $350 billion portfolio of bonds could be in the works as soon as next week.

The data, released this week, showed inflation hit RBA forecast levels years earlier than expected and put pressure on governor Philip Lowe to declare an end to new bond purchases at the bank's 1 February meeting.

The bond buying scheme which costs $4 billion a week will almost certainly be canned next week, said Peter Tulip, chief economist at the Centre for Independent Studies and previously at the Reserve Bank and the Federal Reserve.

He expects Lowe to talk about plans to unwind the balance sheet but delay a formal announcement of a runoff.

Others believe the bank can act more swiftly. With the Fed talking openly about balance sheet reduction, the RBA may feel comfortable ending QE and making a statement about the policy of “runoff” at the same time, Miller said.

“It’s going to be a lot easier for it to abandon quantitative easing and go to some form of quantitative neutrality [balance sheet runoff] now that it knows that most other central banks are going to do the same thing,” he says.